Many songwriters report a disdain for some of their most beloved work, especially if they created it early in their career or it became so successful as to reach cultural saturation. Robert Plant’s dislike of “Stairway To Heaven” is one famous example of this.

But what about when a musician seemingly abandons a masterpiece without so much as a word to why?

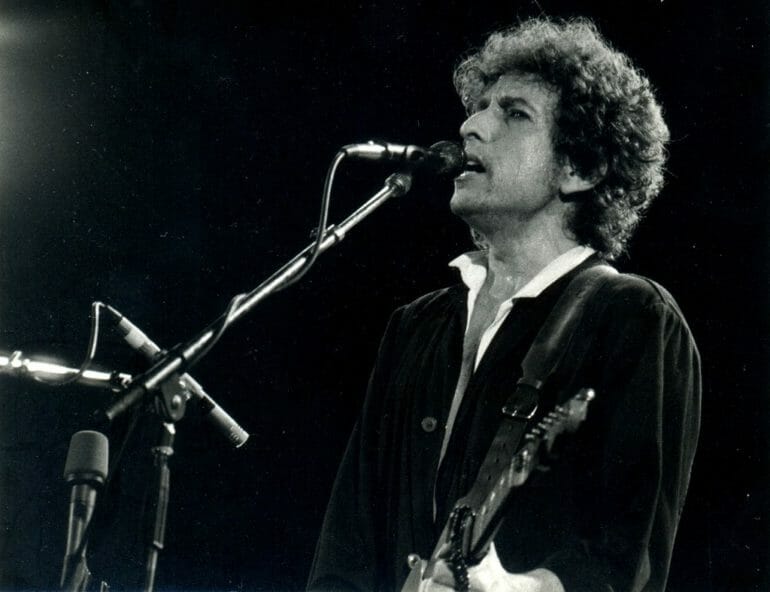

In 1976, this is precisely what Bob Dylan did, silently retiring the unanimously adored track “Hurricane” from his setlist.

Released in 1975, “Hurricane” lights up Dylan’s seventeenth studio album, Desire, like a stick of dynamite on a jail wall, a righteously defiant opening track that unfurls into an 8:33 bisected epic.

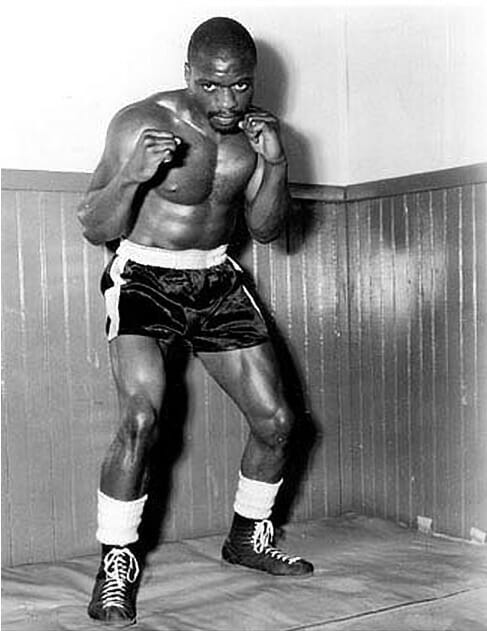

For the uninitiated, the lyrics tell the story of the eponymous Rubin Carter, better known by his boxing alias, “Hurricane”.

It’s a tale of American injustice and racism that follows Carter’s wrongful 1967 triple homicide conviction and his subsequent fight for freedom.

Below is the story of the story!

From Number 1 Contender To Number 45472: A Book Written Behind Bars

Beaten, but not out for the count, Carter refused to fall into obscurity and accept the rotten hand he’d been dealt.

He got to work composing his autobiography, poignantly named The Sixteenth Round: From Number 1 Contender to Number 45472.

The book chronicles Carter’s plight and suffering in the face of a racially biased American judicial system.

Due to his notoriety as a boxer, he was allowed to send out copies of his writings to various celebrities whom he felt would be moved by his cause, one of whom was Mr. Robert Allen Zimmerman.

It’s the account of the incident in this book that Dylan based his song on. But this wasn’t the only research he did. Dylan also took the time to visit Carter in prison on a number of occasions (more on this in a moment!).

Hurricane The Song Vs. Hurricane The Man

Ever the lover of the underdog, Dylan, in his signature drone, tells the story of an innocent black boxer who is framed and sent to prison for triple murder.

But even though this may well be correct, the Hurricane you feel sorrow and rage for in the song is a decidedly different character to the Hurricane Carter of real life.

Born in 1937 as the fourth of what would end up a brood of eight, Carter lived out most of his youth in Clifton, New Jersey, but at the tender age of 12, was incarcerated in the Jamesburg State Home for Boys for stabbing a man with his Boy Scout knife.

Carter claimed that the victim was attempting to sexually assault his friend, but even so, was punished with a six-year sentence.

He managed to escape out a basement window of the reformatory, having served only five of his six years of internment, and two weeks later, at the age of 17, he enlisted in the United States Army.

Stationed in West Germany, he began his boxing training, gaining some early success; however, in 1956, having been court-martialed a whopping four times, he was discharged from the US Army.

He returned from West Germany to pursue a career as a boxer, but not long after his feet made contact with American soil he was accosted and forced to serve the remainder of his initial sentence in the reformatory.

Once ten long months passed by, he was released, only to wind up back in the slammer until 1961 for two muggings.

A Hurricane On The Horizon

Upon his release from Trenton State maximum security prison, he finally got to live out his dream of boxing professionally. At 5’8”, he was significantly shorter than most middleweight boxers but was powerful enough to make the few inches opponents had on him negligible.

By way of his utter speed and ferocity in the ring, not to mention a string of early-round knockouts, his star began to rise, and he was dubbed… “Hurricane”!

Rise Of The Hurricane

In 1965, a short four years after his release from prison, popular boxing publication, The Ring, ranked Carter as the 5th best middleweight fighter in the entire world.

From there, his career suffered ups and downs, amounting to a record of 27 wins, 12 losses, and 1 tie.

Despite this handful of hiccups, he was still considered a real contender for the championship belt, but all his hopes would come crashing down one fateful night in June.

The Night That Changed Everything

There’s a lot that is still up in the air about the murders that Carter ended up doing time for, but here are the cold, hard facts…

- On June 17th of 1966, at around 2:30 a.m. a pair of armed men stormed into the Lafayette Bar & Grill in Peterson, New Jersey, and opened fire.

- Two people were pronounced dead at the scene, the bartender and a customer.

- Another victim died in hospital about a month after the attack.

- A third customer was wounded and survived but was blinded in one eye.

Initially, Carter was cleared by a grand jury after two eyewitnesses (Hazel Tanis & Willie Marins) who described the shooters as “Two Negroes in a white car” could not identify them as the culprits, but the state then managed to produce Arthur Bradley and Alfred Bello.

Upon seeing him, Bradley and Bello picked Carter out as one of the shooters, and he, along with his friend John Artis, who was with him at the time of the incident, was arrested.

But could these two eyewitnesses be trusted?

The Witness Controversy

A black man of significant celebrity and sway in his local area, Carter often used his platform to speak out against the racial prejudice running rife in the police force, so many believe that when the authorities saw their opportunity to get rid of him, they took it.

According to certain sources, Bradley and Bello were petty criminals serving time for burglary and were offered reduced sentences and money to testify against Carter and Artis.

Even though the prosecution was incapable of presenting any concrete motive or evidence against Hurricane & co, this dicey eyewitness testimony was enough to send the pair down with three life sentences, one for each murder.

Rubin “Hurricane” Carter Was An Innocent Man

There is no shortage of people professing their innocence in jails, but Carter stuck to his story vehemently, and during his interment in Rahway State Prison, New Jersey, protested his unjust incarceration by defying prison guards and refusing to wear his inmate’s uniform.

He also began studying and reading voraciously, which would eventually lead to the writing and publishing of his 1974 autobiography.

In The 16th Round: From Number 1 Contender to Number 45472, Carter claims to have had nothing to do with the murders that took place in the bar and eatery that night in June.

What’s In The Mail? Bill, Bill, Bill… Book?

With his autobiography complete, it was time to send it out to whoever might be able to help him with his appeals.

Names on the esteemed list of recipients included fellow boxers Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier, both of whom protested outside the Rahway State Prison walls.

Legendary musicians, singers, and proponents of social justice Joni Mitchell and Joan Baez also received the book and made their stand.

However, none were so captivated by the narrative of Carter’s autobiography than Bob Dylan, who was chosen by Carter as a recipient of his manuscript due to his track record of fighting for civil rights.

Considering Bob’s already extensive catalog of protest songs, it’s no surprise that Carter became something of a muse to the artist.

Hey Hurricane; You’ve Got A Visitor!

The connection Dylan felt with Carter after reading his autobiography only intensified upon meeting the man in the flesh while still imprisoned.

By all accounts, the two clicked instantaneously, talking for hours with Dylan taking notes as they went.

Dylan was reported as saying “I realized the man’s philosophy and my philosophy were running down the same road, and you don’t meet too many people like that.”

Carter revealed that the feeling was mutual when he reported, “We sat down for many, many hours, and I recognized the fact that here was a brother.”

It may seem an unlikely friendship to outsiders, but the truth of the matter is that they likely had a lot to talk about, as Bobby Dylan is a veritable boxing nut!

For those with a rudimentary knowledge of his back catalog, this shouldn’t come as a surprise, as references to the sport are scattered throughout his works.

I can think of four songs right off the top of my head: “Hurricane” (obviously), Who Killed Davey Moore?”, “I Shall Be Free No. 10”, and “The Boxer”.

The Howl Of The Underdog

In all likelihood, Bob was probably well aware of Carter before his arrest due to his accomplishments in the ring, and why not?

Even before the murders, his story was one that seemed to conform to a classic narrative structure.

As one of the smallest fighters in his weight class, Carter was something of an underdog within his own profession, and this pre-existing will to swim against the current and defy the odds only intensified as those odds grew increasingly imbalanced.

He is a living David perpetually facing off against Goliaths.

Carter’s eternal struggle with entities larger than him spoke to Dylan’s Steinbeckian focus on the down-and-outs, to his undying underdogism and desire to make the world a better place.

Jacques Levy: The Cure For Writer’s Block

Despite the wealth of notes taken during his meetings with Carter, Mr. Zimmerman was having trouble getting the right words on the page, so he decided it was time to bring some outside expertise into the equation.

He called on lyricist and director, Jacques Levy, a phenomenal creative who would wind up co-writing the majority of Dylan’s Desire.

Levy’s musical theater background positioned him as the perfect ally to marry storytelling and music in the way Dylan had envisioned but couldn’t yet quite tease out.

When asked about the collaboration, Levy replied that

The first step was putting the song in total storyteller mode, like what you would read in a script:

‘Pistol shots ring out in a barroom night.’

This stage direction-esque line instantly sets the mood and utilizes the present tense to pull the listener kicking and screaming into the grizzly scene.

With such heavy lifting done by very few words, the pair could focus on specific rather than broad strokes as the song unfolded.

The Shortest Of Short Movies

While reflecting on his work with Dylan, Levy spoke of the folk legend’s love of movies and the artist’s uncanny ability to compose miniature movies in song form that “seem as full as or fuller than regular movies.”

Hurricane was one such instance of Dylan’s cinematic approach to lyricism.

And just like in the movies, to express his vision, Dylan and Levy needed to play it pretty fast and loose with some of the details.

The dialogue, for instance, was almost entirely dreamt up by Dylan, as there was really no way of knowing what was said as the incident played out.

The final product drew upon the first-hand account in Carter’s autobiography, the notes he had taken during their meetings, and a multitude of news clippings.

Dylan debuted the song live on PBS broadcast, The World of John Hammond, two months prior to its official single release in November of 75, after which, Hurricane quickly settled into the public consciousness.

The Rolling Thunder Revue Tour

Wherever Dylan landed on his 75/76 Rolling Thunder Revue tour, he played Hurricane without fail — 31 stops, 31 performances of Hurricane!

He was spreading awareness of Carter’s plight across the country and beyond, but the last show of the tour was to be the real drive for justice.

Night Of The Hurricane: “We Gotta Get This Man Out Of Jail”

Known as the Night of the Hurricane, the final stop of the tour was a full-blown benefit concert for Carter, featuring tons of special guests!

Needless to say, Bob played his bard’s retelling of events, stating “We need to get this man out of jail” while introducing the song.

Other notable supporters of Carter, such as Roberta Flack and Muhammed Ali also took to the stage to perform or speak about injustice.

Ali took things a step further by calling Carter and speaking to him from his cell whilst on stage at the concert.

Naming And Shaming

Hurricane is a very confrontational song that deals with controversy head-on, but it also cultivated some unintentional controversy early in its rotation.

The problem? Those named in the lyrics felt they were portrayed in a, shall we say… less than flattering light, namely, Patty Valentine and the two late-game “witnesses”, Arthur Bradley and Alfred Bello.

Valentine was the headlining witness of the prosecution in the initial trials and was not too happy with Mr. Zimmerman.

She even went as far as suing Dylan for defamation in 76, a year after the official song release.

Her lawyers asserted that Dylan’s portrayal of her as a liar was causing significant emotional anguish.

Yet, despite the creative liberties Dylan took with his retelling of events, he remarked that his descriptions involving Valentine were factually correct and that her name was “a piece of thread that holds the song together,”

Dylan refused to change the lyrics of the song and the case was eventually dismissed; however, the bigwigs over at Columbia Records (Dylan’s label) were concerned that more lawsuits would follow unless they took action, forcing Dylan to amend select lyrics in Hurricane.

Hurricane By Bob Dylan – The Lyrics

Okay, that’s most of the background cleared up. Now we can finally put the lyrics of this Bob Dylan masterpiece under the microscope and see what Valentine, Bradley, and Bello were so worked up about!

A Song Of Two Parts

All accounted for, the album version of Hurricane is a mammoth 8:33 long, which, back in the 70s, was almost unthinkable, especially for a folk artist celebrated in the mainstream such as Dylan, so it was decided that the track should be split in two.

On the single, part one could be heard on the A-side, while part two would continue the story after the quick flip of a record.

Spanning 3 minutes and 45 seconds, Hurricane (part one) earned some significant airtime, but the 4 minutes and 47 seconds follow-up was considered a little too unwieldy for radio.

An Incendiary Opening

As mentioned earlier, Hurricane starts by setting the scene…

Pistol shots ring out in the barroom night

Enter Patty Valentine from the upper hall

She sees a bartender in a pool of blood

Cries out “My God, they killed them all!”Here comes the story of the Hurricane

The man the authorities came to blame

For somethin’ that he never done.

Put in a prison cell, but one time he could-a beenThe champion of the world

Patty Valentine lived in the apartment above The Lafayette Bar & Grill and reported that the shots below woke her in the night.

The bartender referenced in the song was James Oliver, one of the fatalities that night.

The Body Count Rises

Three bodies lyin’ there does Patty see

And another man named Bello, movin’ around mysteriously“I didn’t do it,” he says, and he throws up his hands

“I was only robbin’ the register; I hope you understand.”

“I saw them leavin’”, he says, and he stops

“One of us had better call up the cops.”And so Patty calls the cops

And they arrive on the scene with their red lights flashin’

In the hot New Jersey Night

The lyrics referring to Bello’s crime were the ones Columbia Records forced Dylan to amend. Originally, Dylan asserted that he was robbing the victims of the shooting whilst lying dead and wounded on the ground, which Bello was never officially accused of.

The remaining two bodies mentioned in the song were customer Fred Nauyoks (dead) and Hazel Tanis (fatally wounded).

Introducing The Protagonist

Meanwhile, far away in another part of town

Rubin Carter and a couple of friends are drivin’ around

Number one contender for the middleweight crownHad no idea what kinda shit was about to go down

When a cop pulled him over to the side of the road

Just like the time before and the time before thatIn Paterson, that’s just the way things go

If you’re black, you might as well not show up on the streetLess you want to draw the heat.

As mentioned earlier, at the time of his arrest, Carter was considered a shoo-in for the middleweight title, which is laid out in black and white in the lyrics.

What isn’t presented in the song is the fact that Carter had a history of violence and theft.

The line “Just like the time before and the time before that” implies that any dalliances Carter had with the law prior to this event all boiled down to systematic racism, which isn’t entirely correct.

Of course, many might argue that Dylan is referring to racial profiling in a more general sense, rather than pertaining to Carter specifically.

It’s all up for interpretation, but the lyrics do seem to omit some of the ugly details.

Bello Didn’t Act Alone

Alfred Bello had a partner, and he had a rap for the cops

Him and Arthur Dexter Bradley were just out prowlin’ aroundHe said, “I saw two men runnin’ out; they looked like middleweights

They jumped into a white car with out-of-state platesAnd Miss Patty Valentine just nodded her head

Cop said, wait a minute, boys; this one’s not dead

So they took him to the infirmary

And though this man could hardly seeThey told him that he could identify the guilty men

Bello and Bradley were fixing to rob a factory in the area that night, which is why they were around and able to witness events at The Lafayette Bar & Grill.

The surviving victim was Willie Marins, blinded in one eye by the shots. Despite his impaired vision, the police told him he could stand as a suitable witness for the prosecution.

The Arrest

Four in the morning and they haul Rubin in

They took him to the hospital and they brought him upstairsThe wounded man looks up through his one dyin’ eye

Says, “Wha’d you bring him in here for? He ain’t the guy!”Here’s the story of the Hurricane

The man the authorities came to blame

For somethin’ that he never done

Put in a prison cell, but one time he could-a beenThe champion of the world

Both the original witnesses – the fatally wounded Tanis and the blinded Marins – claimed the murderers were black, but neither identified Carter or Artis as the culprits.

On the contrary, Marins specifically testified that Carter was not one of the shooters. Alas, his account fell on deaf ears.

Turmoil In Cleveland, Ohio

Four months later, the ghettos are in flame

Rubin’s in South America, fightin’ for his nameWhile Arthur Dexter Bradley’s still in the robbery game

And the cops are puttin’ the screws to him, lookin’ for somebody to blame.“Remember that murder that happened in a bar?

Remember you said you saw the getaway car?You think you’d like to play ball with the law?

Think it might-a been that fighter that you saw runnin’ that night.Don’t forget that you are white.”

This verse opens with a reference to the Hough riots. These were a sequence of racially charged conflicts that took place between July 18 and July 23 of 66.

Due to the prolific use of firebombs, the entire area ended up ablaze

Although these riots took place elsewhere, their mention informs the listener of intensifying racial tensions across the States.

This verse also, in no uncertain words, accuses the law of conspiracy to imprison an innocent man via bribery and perjury.

Allegedly, they used Bradley’s criminal past and convictions to coerce him into giving false testimony.

Arthur’s Decision

Arthur Dexter Bradley said “I’m really not sure.”

The cops said “a poor boy like you could use a breakWe got you for the motel job and we’re talkin’ to your friend Bello

You don’t want-a have to go back to jail; be a nice fellowYou’ll be doin’ society a favor

That son-of-a-bitch is brave and gettin’ braverWe want to put his ass in stir

We want to pin this triple murder on himHe ain’t no Gentleman Jim.”

Here, Dylan uses the rhetoric of the police to highlight their racism.

They mention that Carter “ain’t no Gentleman Jim”, referring to James J. Corbett, a white man considered to be the father of modern boxing.

The police are positioning Carter’s blackness in binary opposition with the gentlemanly Corbett, thus presenting blackness itself as uncivilized.

Professional Violence Vs. Illegal Violence

Rubin could take a man out with just one punch

But he never did like to talk about it all that much“It’s my work,” he’d say, “and I do it for pay.”

“And when it’s over, I’d just as soon go on my way

Up to some paradise

Where the trout streams flow and the air is nice

And ride a horse along a trail.”But then they took him to the jailhouse

Where they try to turn a man into a mouse

This verse paints Carter as a peaceful individual, distancing his professional violence from the Carter of everyday life, thereby asserting his innocence.

The Second Trial

All of Rubin’s cards were marked in advance.

The trial was a pig-circus; he never had a chanceThe judge made Rubin’s witnesses drunkards from the slums

To the white folks who watched, he was a revolutionary bumAnd to the black folks, he was just a crazy n****

No one doubted that he pulled the triggerAnd though they could not produce the gun

The DA said he was the one who did the deedAnd the all-white jury agreed.

Next up, Dylan targets the retrial, drawing attention to the lack of hard evidence and the prejudice of the “all-white jury”.

An illegitimate Trial

Rubin Carter was falsely tried

The crime was murder one… guess who testified?

Bello and Bradley and they both baldly lied

And the newspapers, they all went along for the rideHow can the life of such a man

Be in the palm of some fool’s hand

To see him obviously framed?

Couldn’t help but make me feel ashamed to live in a land

Where justice is a gameNow all the criminals in their coats and their ties

Are free to drink martinis and watch the sun rise

While Rubin sits like Buddha in a 10-foot cell

An innocent man in a living hellThat’s the story of the Hurricane

But it won’t be over ‘till they clear his name

And give him back the time he’s done

Put in a prison cell, but one time he could-a beenThe champion of the world.

Finally, Dylan places himself into the narrative, giving his opinion that the second trial was a sham and that he’s ashamed to live in America.

He also equates Carter with Buddha, again, building an image of peace and innocence.

The Aftermath Of Dylan’s “Hurricane”

Dylan effectively ends his bitter tale with an implied call to action, rousing the people to protest for justice, and challenging the authorities to right the wrongs that placed Carter behind bars… and people listened!

A second benefit show (Night of the Hurricane II) was held featuring musical giants such as Stevie Wonder and Stephen Stills, and less than two months later, Carter was released on bail and offered a retrial, but the happy ending Dylan was hoping for wasn’t to arrive.

History Repeats Itself

Despite the eyewitnesses retracting their earlier testimonies, Carter and Artis were once again found guilty in the 76 retrial.

But it’s not just Hurricane the man that was taken away that day. After the news broke, Dylan dropped Carter’s cause from his agenda and permanently retired Hurricane, the song.

Perhaps it was due to utter disillusionment with the justice system and the rampant racism of 70s America.

Maybe he felt the early momentum the track cultivated was spent, and that it would gradually become a mere entertainment piece as opposed to a fiery protest song.

A Championship 27 Years In The Making

Despite Dylan’s silence on the topic, in 1985, New Jersey Federal District Court Judge Haddon Lee Sarokin, overturned Carter’s conviction, stating that the retrial was:

predicated upon an appeal of racism rather than reason, and concealment rather than disclosure.

A then 48-year-old Carter was released after just shy of a two-decade stint in the slammer, the majority of which had been endured in solitary confinement.

Eight years later, Carter would be awarded a 1993 honorary World Championship title, but his days fighting in the ring were well and truly over.

His new opponent was injustice, a foe he sparred with as head of the Association in Defense of the Wrongly Convicted, and later, in 2004, as the founder of Innocence International.

Bob Dylan’s Hurricane Remains Unfinished

Dylan states that the story of the Hurricane “won’t be over ‘till they clear his name”, But, unfortunately, this never happened.

The conviction was overturned on the basis that the retrial was unlawful, not that Carter and Artis were innocent.

What The Hurricane Left Behind

Both Rubin’s book and Dylan’s “Hurricane” held a mirror up to the American justice system and society as a whole.

These works of art shifted the cultural landscape by spreading awareness of injustice and racial discrimination, and a number of subsequent releases carried on the fight they started.

Countless Carter biographies have been penned, and in 1999, Denzel Washington starred as Carter in the movie, Hurricane.

Final Thoughts

Sadly, in late April 2014, Carter succumbed to the symptoms of prostate cancer and passed away, but, despite Dylan’s silence, his legacy of righteous recalcitrance lives on.

Hurricane the song went on to become Dylan’s fourth most popular of the decade, landing well into the top half of the Billboard Hot 100, yet to this day, he refuses to play it live.

It’s been covered many times by big-name artists, but the last time Zimmerman himself uttered those lyrics that shook America was Night of the Hurricane II, and it appears as if that’s exactly how things are going to remain!

To see the legendary Bob Dylan perform Hurricane live in 1975, have a look at this video from the Swingin’ Pig. Hearing Dylan sing this song never fails to give me goosebumps.

- The 25 Richest Rock Stars in the World | A Rock And Roll Rich List - February 22, 2024

- Rock And Roll Movies | 20 Films That Will Rock Your World - February 19, 2024

- The Biggest One Hit Wonders In Rock History - February 16, 2024