People love pop music: there’s no doubt. My friends have themselves engaged in an online movement known as Poptimism. It’s very promising and highly rewarding. The concept is rather simple if the name doesn’t already give it away.

Pop music is often swept under the carpet, by critics, music publications and even by audiences. A pop song’s existence is often marked by its disposable consumption: a few weeks in the charts and then it’s gone. As such, they often lend themselves to simpler forms and structures and very rarely stray from a few select topics lyrically.

This doesn’t make them bad, by any means. Everybody loves to dance. The problem arises when the same thing happens to albums that can be appreciated for their artistic value: they get caught up amongst the albums that listeners would otherwise find disposable.

What I appreciate most about the Poptimists is the outlook. I’m sure we can all admit that there are bad pop songs, but that doesn’t stop the Poptimists from searching for the good ones, reminding others of their quality and ensuring a good work of art gets the recognition it deserves.

Talk Talk

Mark Hollis’ New Wave pop outfit Talk Talk had quite a few successful synthpop and art-pop anthems before their experiments in post-rock, including “Life’s What You Make It,” “It’s My Life,” “Today,” and so on. Although they charted well, “Today” reached No. 14 in the UK charts, these songs have less of a reputation now than their counterparts.

Embed from Getty ImagesFans who loved Talk Talk back in the 1980s, of course, have never forgotten the lyrics to these songs, but new fans have formed a cult around the band’s final three albums. Like savants, they preach of the infinite dynamism, elasticity, and formlessness of the album.

They tell you about its towering crescendos, the eruptions of noise, about how Mark Hollis sings the lyrics as if he were preaching, about how the album moves from fear to redemption, acceptance. All of them are nice (and probably useful) observations, but none have told you how enjoyable it is to listen to.

Technical observations and figurative descriptions of sound are largely unavoidable when talking about music, but they don’t typically sell an album. How many people could convince a friend (who wasn’t a music buff) to listen to something by telling them the time signature a song is written in? By telling them that it’s modal? By telling them that a song is “formless”? To most people, it’s not useful information. Most of the time, a more basic and relatable comparison is helpful.

People fear experimental music and for good cause: it so often appears pretentious and masturbatory. And while I do agree, I also believe experimental music is a well of infinite inspiration and discovery. Hollis has even confessed his fear of “intellectualis[ing] music”. And despite changing the sound of the band entirely, Hollis professed that he was (and had always been) concerned with the “spirit” of music much more than the “technique.”

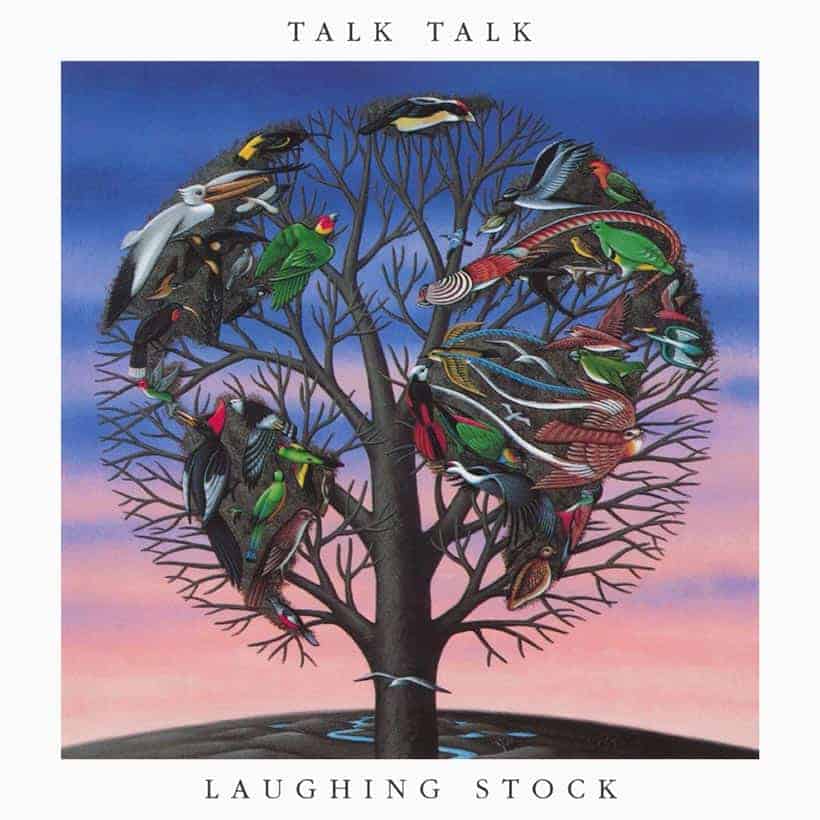

Talk Talk Laughing Stock

There is nothing to be fearful of when listening to Talk Talk. Although Laughing Stock feels organic and unfamiliar, it is almost instantly rewarding. You do not need to be a wizard of musical theory, a jazz hermit or a rabid bohemian to enjoy any of the sounds that flower and jump out of this album. For me, the very first listening experience was much like a pop song: instantly enjoyable, satisfying, complete almost.

Unlike pop, Laughing Stock often doesn’t have a predictable form or structure. The climactic moments of the album are often delivered in strange and unusual ways. “After the Flood,” for example, has a howling noise that almost disrupts the entire droning and repetitive sensation created by everything that comes before.

The feelings a listener might experience across the entire album are incongruous. Snow in Berlin, a Mark Hollis and Talk Talk resource site, aptly describes the album as “one long piece spanning an evolution of moods.”

“Myrrhman,” for example, feels solitary, dark and contemplative and closes with dirge-like strings, only to be thwarted by the massive sound of hammering chords that follow on the next track, “Ascension Day.” In this song, there seems to be something prophetical, anticipatory as Hollis sings “farewell” and considers “judgment day.”

Towards the end of Talk Talk’s Laughing Stock, something feels as though it has been accomplished or realized. The spirit of the music and the speaker feels as though it has completed its journey of “ascension.”

“New Grass,” the penultimate track offers a delicate sense of optimism, an upwards sensation, a brightness, a rebirth. The final song, “Runeii,” is austere and it feels like a bookend to the album, characterized best by its silence and empty spaces.

“The silence is above everything, and I would rather hear one-note than I would two, and I would rather hear silence than I would one-note” was the philosophy with which Hollis approached these new musical endeavors.

The production process had grown more meticulous by the time the band arrived at Laughing Stock. They had left EMI records for the jazz-based Verve Records label which promised creative freedom, recruited some highly experienced sound engineers (Like Tim Friese-Green) and attempted to conceptualize the album, as well as create it.

“Windows were blacked out, clocks removed, and light sources limited to oil projectors and strobe lights.” Wyndham Wallace writes of Wessex Studios, according to an account given by sound engineer Phil Brown in The Quietus.

“It was a unique way to work. It took its toll on people, but gave great results”

The album was no small feat. Phil Brown claims that the entire album took around a year “to record, mix and master… It was a unique way to work. It took its toll on people, but gave great results.” Although fifty musicians contributed to the recording process only eighteen made it on to the album.

Their contributions were largely the result of a tedious system improvisation in which musicians would play as they liked, with a general focus on the mood of the song. The yield, the usable parts of their contributions, were microscopic.

Hollis recalled, “Ten hours playin’ back on somethin’ to get a few seconds… ninety percent of what you play will be rubbish.” Hollis made the perspective of space paramount in the albums recording, commending works like “In A Sentimental Mood” by Coltrane and “Tago Mago” by Can for the intimacy they afforded the listener.

It’s true. The sound achieved on Talk Talk’s Laughing Stock is achingly proximate. It can sound rueful and delicate, empyrean, divine and full of optimism, fearful and towering all in a moment’s fall. Moments of silence are loaded with electric anticipation. Never do you feel like something predictable is arriving next.

Embed from Getty ImagesAs one sonic zenith passes another is fermenting, and when we are left to dwell in the calm and verdant dales of Laughing Stock, there is plenty of scenery to appreciate. A full landscape is painted and animated by the sense of perspective Hollis infused, focusing so much on the sound of “space” and silence. Alone we explore, on a journey that feels incredibly natural and atmospheric. The high points feel religious; the quiet moments feel introspective and delicate.

The way I can best summarise the enjoyment I experienced when listening to the album is by comparing it to the instant reward of pop music. When I first listened to Talk Talk’s Laughing Stock, it felt immediately compatible. But like good pop music, the innovations are not there merely to service the form, but to contribute to an artistic concept.

In other word’s Laughing Stock’s experimental aspects are not merely technical achievements but aesthetic ones. The result is crystalline. Hollis wrestled with labels, engineers, very talented musicians, his fans and the music industry holistically (excuse the pun) to ensure his vision was realized in the purest form.

In the words of Alan McGee, “I find the whole story of one man against the system in a bid to maintain creative control incredibly heartening.”

Written by Tom Westhead.

Listen to Talk Talk’s Laughing Stock Here

Some links may be affiliate links. We may get paid if you buy something or take action after clicking one of these. We do this to help support the site.

Similar Articles…

- The Alice Cooper Fact Sheet – 5 Things You Need To Know - January 12, 2023

- Everybody Knows The Words, But What Is Hotel California About? - April 29, 2022

- What Is The Meaning Of Stairway To Heaven: Led Zeppelin’s Amazing 1971 Musical Epic? - April 24, 2022