On October 28th, 1956, a twelve-year-old Townes Van Zandt got his first glimpse of rock ‘n’ roll. Elvis Presley made a legendary appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show in all of his flamboyant, show-boating glory. The young Townes’s life was never the same again.

What made the biggest impression on him was the way Elvis worked a guitar. And though his musical career was to diverge significantly from the template laid out by the King, Townes always reflected on that moment as a defining one in his life.

Who Was Townes Van Zandt?

Townes Van Zandt was born to a wealthy family in Fort Worth, Texas. He was an intelligent student and worked hard. His high IQ led to his family’s attempts to turn him into a doctor or lawyer, or another such prestigious personage. But it wasn’t to be.

In 1962 he began studying at the University of Colorado, but the academic lifestyle did not suit him. He quickly descended into alcoholism and depression and wound up spending time at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston, where he was diagnosed with manic depression.

For three months he was subjected to controversial insulin shock therapy, leaving him comatose for lengthy periods of time, and erasing the bulk of his long-term memory. When he emerged from his treatment, Townes set about rebuilding his life.

He was already an avowed music lover, idolizing blues and folk legends like Lightnin’ Hopkins and Bob Dylan. He began playing occasional shows at clubs in and around Houston, the setlists primarily comprising covers of his favorite songs.

The music was better therapy than any he received in a hospital, and he was duly encouraged by his parents. But at the same time, he was still determined to pursue the path of respectability. In ’65 he was accepted onto the pre-law program at the University of Houston, yet he remained restless. His subsequent attempt to join the Air Force proved a non-starter because of his bouts of mental illness. He eventually dropped out of college in 1967.

Free of the constraints of the middle-class student lifestyle, Townes let his creative ambitions thrive. He stepped up his live performances and began writing original material. He became a regular face on the folk-centric coffee shop circuit of Houston, Texas. But his career as a professional musician and songwriter did not really take off until 1968, when he upped sticks for the cultural hub of Nashville, Tennessee.

Embed from Getty ImagesThere he met legendary record producer “Cowboy” Jack Clement. Clement had written and produced a lot of material for Johnny Cash including the number one hit “Ring of Fire.” Townes and Clement hit it off, and the young folk musician found himself on the fringes of the big-time.

RELATED: The Life And Time Of Tammy Van Zant

Townes Van Zandt Albums

The very first Townes Van Zandt album, For the Sake of the Song, was released in late 1968. However, it proved ultimately a problematic record that confounded Townes’s folk and country fanbase. It was a colossally overproduced affair, with extensive use of effects and technical trickery which seemed to bury the fragile simplicity of the original compositions.

But one undeniable feature was the quality of Townes’s songwriting. The raw poetry of numbers like “Tecumseh Valley,” “I’ll Be Here in the Morning” and “Waitin’ Around to Die” shone through the fuzz.

When it came to his second album, Our Mother the Mountain, the production was wisely tempered down. The natural beauty of songs like “Be Here To Love Me” and “My Proud Mountains” was allowed to shine. The album also featured a re-recording of “Tecumseh Valley,” which was Townes conceding that the original version on his previous album did not do the work justice.

Our Mother the Mountain was recorded in LA and released in April of ’69. Throughout this time, Townes was living the life of an authentic folk troubadour. Hitching his way across the United States with a guitar slung on his back, sleeping in motel rooms or under the stars. He was the real deal.

Album number three, simply titled Townes Van Zandt, continued the winning streak. Though none of his albums could reasonably be described as big sellers, they all attracted critical acclaim and boosted Townes’s steady rise to prominence as an artist.

Embed from Getty ImagesBut they were never going to make him a millionaire. This album featured ten more exquisitely crafted originals, plus four re-workings of numbers from For the Sake of the Song, with which Townes was vocally dissatisfied.

His fourth album, 1971’s Delta Momma Blues, brought something of a change in direction. Rather than the countrified folk ballads which had brought him to popular acclaim, the songs on this one were noticeably bluesier.

The standout tracks, and the ones which have stood the test of time best, are the last two. These are dark little numbers indeed, “Rake” and “Nothin’.” Now Townes seemed to have struck on a winning formula, his albums were simple and stripped-back affairs, without any unnecessary adornment.

Number five, High, Low and In Between, which came out in late ’71, was yet another frustratingly underwhelming commercial performer. For a songwriter with undeniable chops and a cult following that was going global, Townes was never destined to have a crossover hit as a solo performer. This album boasts a slightly more rock-centric style, and includes one of his masterpieces, “To Live Is To Fly.”

Album number six, The Late Great Townes Van Zandt, is considered by many to be his finest work. It features his two signature numbers, “Pancho and Lefty” and “If I Needed You.” It is widely acknowledged as one of the quintessential American albums. But it also marked the end of an era.

Poppy Records, the company run by Jack Clement which had produced every Townes album up to this point, was dwindling. Also, tensions between Clement and Townes’s manager Kevin Eggers were close to boiling point.

This culminated in an ugly incident when every track for a proposed seventh album, Seven Come Eleven, was erased by Clement in a fit of anger. Fortunately, Eggers had recorded the rough mixes onto cassette tape. The songs were eventually released on the compilation The Nashville Sessions.

Perhaps disillusioned by the bickering behind the scenes, Townes did not record another album until 1978. He was also deeply mired in substance abuse throughout, descending into alcohol and heroin addiction. But he continued to perform live in dive bars across the country, to small but devoted audiences.

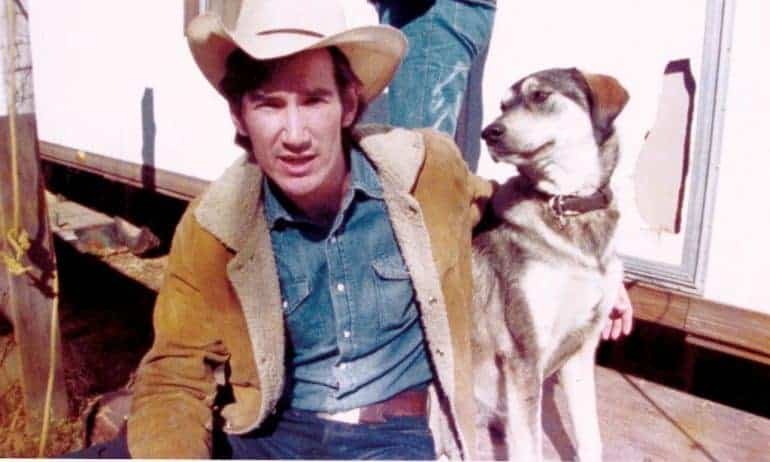

Ramblin’ Lifestyle

A valuable record of Townes Van Zandt’s lifestyle at that point can be found in the documentary film Heartworn Highways, which was filmed in 1975 but not released theatrically until 1981. In the film, we see Townes in his natural habitat, his trailer park home in Austin, Texas. It provides an insight into his hard-living ways, depicting the singer downing whiskey from the bottle and indulging in a little gunplay.

Townes’s drug use from the ’70s through to the end of his life was heavy. Accounts from friends depict him openly shooting up heroin in public (including in front of his eight-year-old son). As well as performing drunk, forgetting his lyrics and losing the ability to play guitar.

He was in and out of rehab various times in his life, but it never quite seemed to stick. This tragic state of affairs led to Kevin Eggers’s brother Harold being employed as a caretaker for Townes, keeping him out of trouble on the road.

Embed from Getty ImagesTownes did everything he could to shun celebrity. Though he and Bob Dylan were mutual admirers, Townes declined the opportunity to record with his hero on account of a dislike for the celebrity culture with which Dylan was inescapably associated.

He lived the life of a hermit, in a shack without plumbing or electricity. In the mid-’70s, he also parted ways with Eggers. Both literally and figuratively, these were his wilderness years. The stagnation was not good for Townes, and his drug addiction significantly worsened.

But come 1978, he experienced a change of heart and re-hired Eggers before releasing another full studio album: Flyin’ Shoes. This featured re-recorded versions of a lot of the lost songs from the Seven Come Eleven sessions.

The album was yet another sleeper hit, further reinforcing Townes Van Zandt’s reputation for songwriting craftsmanship and raw, emotive vocal performances. Significantly, though, it featured a few new compositions.

The bulk of the songs had in fact been written years before. This perhaps indicates a sense of burnout that Townes was experiencing at the time. No doubt exacerbated by his drug use. He would not record another album for nine whole years.

However, throughout the 1980s, his career experienced a pronounced up-turn thanks to a number of highly successful cover versions of his songs by other artists. This is the closest Townes ever came to mainstream success. Emmylou Harris and Don Williams recorded “If I Needed You” in 1981, taking it to number three in the country charts.

Then in 1983 country music legends Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard recorded “Pancho and Lefty” as a duet that went all the way to number one.

Throughout the ’80s, Townes toured less and less frequently. His drug abuse and alcoholism had taken a toll on his vocal abilities. He spent much of his time simply living off the residuals he was making from the other artists who covered his songs.

He did, however, make one or two TV appearances. This exposed his music to new audiences and helped to sustain his legend. His domestic situation settled down considerably, with his third wife Jeanene giving birth to a son, Will.

But he did record an album in 1987, titled At My Window. Again, this featured a lot of off-cuts from previous albums that Townes Van Zandt re-recorded. But, all the same, the album was met with dazzling critical plaudits and frequent comparisons with another fabled journeyman songsmith, Hank Williams.

In his performing and in himself, Townes seemed more laid-back these days. His drug abuse had dwindled and he seemed happy. He was however still a practicing alcoholic. The longest period of sobriety he ever enjoyed took place over about a year between 1989 and 1990. But when he lapsed again, it was clear that he was on a path to self-destruction like so many tortured artists before him.

By the early ’90s, Townes’s friends and admirers noted how frail he had become. This was the long-term impact of his lifetime of substance abuse. An attempt to detox in 1994 got nowhere. In that same year, he recorded what was to be his swan song: No Deeper Blue.

Embed from Getty ImagesThis was an album recorded and produced in Ireland by Phillip Donnelly, who had played guitar on Flyin’ Shoes way back in ’78. Interestingly, all fourteen songs were original compositions and represented Townes’s last great bout of creative work. His lyrics are by turns sweetly nostalgic and harrowingly dark. They are a poignant summation of what Townes’s life had by then become.

A few days before Christmas of 1996, Townes suffered a fall at his home, injuring his hip. This left him in tremendous pain and unable to move. But he refused to go to a hospital for eight full days. Jeanene made one last attempt to get him to detox, though doctors advised that he would be better off attempting it under medical supervision.

All the same, Jeanene checked Townes out of the hospital and drove him home. He drunk a flask of vodka to ward off the delirium tremens. This restored him to lucidity and turned him back into his affable self. But it wasn’t to last.

That night, New Year’s Eve, he fell asleep in bed at home and lapsed into a coma. In spite of Jeanene’s efforts to perform CPR, he died in his sleep in the early hours of January 1st, 1997. He was 52 years old.

Townes Van Zandt’s death was met with an outpouring of grief from the music community. In spite of his flaws, he has left behind him a remarkable legacy. He was a genius and a legend in his own time.

Similar Stories…

- Ronnie Van Zant – Southern Rock’s Golden God

- Lowell George – The Little Feat Frontman That Died Too Young

- The Alice Cooper Fact Sheet – 5 Things You Need To Know - January 12, 2023

- Everybody Knows The Words, But What Is Hotel California About? - April 29, 2022

- What Is The Meaning Of Stairway To Heaven: Led Zeppelin’s Amazing 1971 Musical Epic? - April 24, 2022